In December, my husband, our 5-year-old daughter and I examined constructive for COVID-19. Life, already off-kilter, lurched. Scent, style, breath — have been they regular? The air smelled solely of chilly; all the things tasted vaguely of cardboard.

The state mailed us a pulse oximeter to learn oxygen ranges from our fingers. The gadget beeped when these ranges dipped too low — a seemingly goal measure throughout a subjective time. We used the gadget with abandon, solely my husband frequently triggering the alarm. He went to mattress, the place he stayed for days, or perhaps it was weeks. Time distilled into moments: distant college, meals, Christmas, pulse-ox, beep.

We exited quarantine on January 1, the day of recent begins. Besides my as soon as energetic 8-year-old son, who in some way by no means examined constructive, now loafed in entrance of the heater for hours. My husband, his respiratory nonetheless irregular and his fatigue lingering, raged. Ever the extrovert, I absorbed their feelings as my very own. My threat calculation shifted, as despair overshadowed the concern of illness. The illness we had hid from for thus lengthy had discovered us anyway. Have been we now immune? Ought to we proceed simply as earlier than?

Previous to the illness, I’d been researching pandemic fatigue, a time period used to explain the boredom that may come up throughout a protracted disaster just like the one we’re in now (SN On-line: 2/15/21). “Folks desire motion to inaction,” social psychologist Erin Westgate of the College of Florida in Gainesville instructed me. For some, that compulsion towards the experiential runs deep, she and colleagues reported in 2014 in Science. When the researchers gave school college students a selection between sitting idly in a quiet room or pushing a button to obtain an electrical shock, a startling quantity went for the shock.

I’ve been looking for, and pushing, that button all my life. I’ve taught English in Japan, labored as a nationwide park ranger and, following an unlucky collection of occasions, offered pineapples alongside a vacationer freeway in Hawaii in trade for a tent over my head. Westgate’s current work means that button pushing kinds typically flourish in wealthy and aesthetic environs. I took heed. Towards the dreary backdrop of being homebound in a world well being disaster, I signed up for personal pottery classes, drawn viscerally to the thought of making one thing from mud.

Author Sujata Gupta has been taking pottery classes for a brand new aesthetic expertise.Sarah Camille Wilson

A 3rd path

Psychologists who examine well-being or human flourishing have lengthy posited that the “good life” will be pursued through two paths: happiness or that means.

“To this point, psychologists labored with this dichotomy — a dichotomous mannequin of well-being about life,” says psychologist Shigehiro Oishi. He describes the completely satisfied life as considered one of pleasure, consolation and safety, and the significant life as considered one of significance, goal and coherence, or order. Happiness and that means can run parallel or intersect, Oishi says. Each ideas are largely rooted in private and societal stability.

What occurs, although, when the bottom beneath one’s ft buckles? Or what if one was by no means fairly steady to start with? What hope is there for locating a path to the great life?

For the final six years, Oishi and his group on the College of Virginia in Charlottesville have been hammering out their response: a 3rd path to the great life coined “psychological richness.” Their analysis means that the elements of a wealthy life come not from stability in life circumstances or in temperament. Reasonably, the trail to a wealthy life arises from novelty looking for, curiosity and moments that shift one’s view of the world. Wealthy experiences are neither inherently good nor dangerous; they might be intentional or unintended, joyous or traumatic.

The pandemic, on this gentle, embodies a novel, perspective-changing, psychologically wealthy second. It has shattered our routines and livelihoods, robbed us of our family members and plunged many into despondency. But it surely has additionally steered a few of us to the mud. Now we have captured wild yeast for sourdough breads, planted gardens and knitted sweaters; we have now stared at a moist mound of clay on a wheel and questioned, what subsequent?

This third good life path can present a balm in troublesome occasions, says Westgate, Oishi’s former graduate pupil. “Psychological richness opens up an avenue to the great life for individuals for whom circumstances might appear to have reduce off paths to happiness and that means.”

Aristotle’s legacy

If you wish to perceive psychological richness, examine Oliver Sacks, advises Lorraine Besser, a thinker at Middlebury Faculty in Vermont and Oishi’s collaborator. She is considering of an adieu to the world that Sacks wrote within the New York Occasions in February 2015, shortly after studying he was dying of most cancers.

The famend writer and neurologist drew his inspiration from thinker David Hume, who had written an identical adieu in 1776. Hume described himself as possessing a “gentle disposition,” Sacks wrote. “Right here I depart from Hume. Whereas I’ve loved loving relationships and friendships and haven’t any actual enmities, I can not say (nor would anybody who is aware of me say) that I’m a person of gentle tendencies. Quite the opposite, I’m a person of vehement disposition, with violent enthusiasms, and excessive immoderation in all my passions.”

Historical discussions of the great life don’t seem to contemplate Sacks’ mannequin. As an alternative, fourth century B.C. Greek thinker Aristotle looms massive on this esoteric house. He opens his treatise, Nicomachean Ethics, by reviewing the assorted contenders for the great life — pleasure, honor, wealth, well being or eminence — finally arriving at “eudaimonia,” primarily human flourishing. The eudaimonic individual, Aristotle wrote, “is energetic in accordance with full advantage … not for some unspecified interval however all through an entire life.”

Signal Up For the Newest from Science Information

Headlines and summaries of the newest Science Information articles, delivered to your inbox

Of these contenders, solely pleasure and eudaimonia, the “feeling good and being good” sides of that dichotomous coin, have withstood the lengthy check of time, Westgate says.

Aristotle, an unequivocal be-gooder, thought-about the great life an goal best. So does Susan Wolf. “Some philosophers, together with me, say a great life isn’t simply good from the within,” says Wolf, an ethical thinker on the College of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. As an alternative, a life should even be good from the surface, or from the attitude of 1’s neighborhood.

However the emergence of constructive psychology a number of many years in the past shifted consideration from the collective to the person. Now, Westgate says, “whether or not or not it’s a great life is de facto within the eyes of the one who led that life.”

Sacks’ imaginative and prescient

Sacks’ early years have been marked by heartache, based on a documentary of his life that aired on PBS in April. Born in 1933 in London, Sacks was despatched to a boarding college throughout World Warfare II, the place the opposite youngsters bullied him and his older brother, Michael. In that setting, Michael turned psychotic and was identified with schizophrenia. The household was devastated. Then, when Sacks was 18, his mother and father found he was homosexual. His mom, with whom he shared an in depth bond, referred to as him an “abomination.”

“Her phrases haunted me for a lot of my life and performed a significant half in inhibiting and injecting with guilt my sense of my very own sexuality,” Sacks stated.

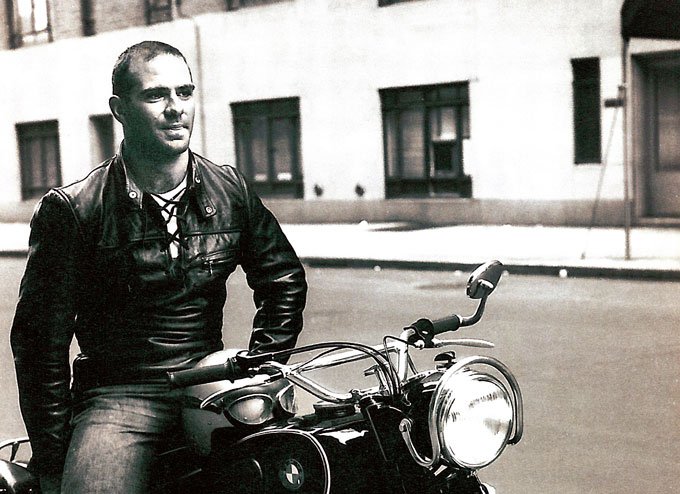

Sacks fled to San Francisco on his twenty seventh birthday and interned at a medical heart. Off hours, Sacks muscled up, finally lifting a 600-pound bar from a squat to set a California weight lifting file. He additionally acquired hooked on amphetamines, thereby sleeping and consuming little, whereas roaring excessive and quick on his motorbike. Sacks, the documentary suggests, was working from his personal overwhelming loneliness.

“That type of sensitivity is harmful. It requires a level of urge for food, vitality, a responsiveness, which signifies that you can go off the rails at any second,” the documentary’s director Ric Burns tells me. “The query turns into: What’s the relationship you’re going to must your individual appetites?”

When neurologist Oliver Sacks was in his late 20s, as proven right here in 1961 in Greenwich Village, N.Y., he was residing a wild, but solitary life.The Oliver Sacks Basis

When neurologist Oliver Sacks was in his late 20s, as proven right here in 1961 in Greenwich Village, N.Y., he was residing a wild, but solitary life.The Oliver Sacks Basis

On New 12 months’s Eve 1965, Sacks stared into the abyss of his drug dependancy. “I checked out my emaciated face and I stated, ‘Oliver, you’ll not see one other New 12 months’s Day until you get assist,’ ” Sacks recalled within the documentary.

Six months later, Sacks started seeing migraine sufferers at a clinic in New York Metropolis. Throughout what would transform his final amphetamine excessive, Sacks learn a 500-page e book on the idea behind migraines, with detailed case research, written by doctor Edward Liveing within the 1870s. “I learn by the entire e book in a state of ecstasy,” Sacks stated. “With the amphetamines in me, typically it appeared to me that the neurological heavens opened and that the migraine was shining like a constellation within the sky.”

After that imaginative and prescient, Sacks started writing detailed accounts of his sufferers’ experiences, a course of that merged his mental and inventive passions. Embarking on this psychologically wealthy literary journey would maintain Sacks all through his life.

Past the dichotomy

In fall 2015, Westgate was a graduate pupil in Oishi’s lab. With lab members squeezed into his tiny workplace for a gathering, Westgate remembers, Oishi walked in and requested: “Is happiness and that means all there’s?”

That assembly and the following dialogue marked a turning level for Oishi. He had, like most well-being researchers, been publishing papers that labored throughout the happiness-that means dichotomy. But he had grown disillusioned by these paths’ shortcomings. As an example, why, as analysis has persistently proven, did happiness hinge on having significantly more cash than is strictly mandatory? And why did homogenous good friend circles give individuals extra happiness and satisfaction of their lives than numerous circles?

After that assembly, Westgate remembers, the group homed in on one query: If you happen to lack cash and stability, can you continue to have a great life?

The group seemed for a 3rd path, one stuffed with wealthy, aesthetic experiences. First the group developed a scale to measure psychological richness. The size mirrored these used to measure happiness and that means. Respondents rank 17 statements from 1 for strongly disagree to 7 for strongly agree. Statements embody: “On my deathbed, I’m more likely to say ‘I had an attention-grabbing life’ ” and “My life would make a great novel or film.” The outcomes, showing June 2019 within the Journal of Analysis in Character, confirmed that scoring excessive in a persona trait often known as “openness to expertise” predicted excessive richness scores however not essentially happiness or that means.

Later analysis revealed that folks excessive in richness are additionally emotionally intense, vulnerable to experiencing robust constructive and adverse feelings. Folks excessive in that means and happiness, in the meantime, expertise constructive feelings extra strongly than adverse feelings.

To see how the three paths — happiness, that means and richness — play out throughout life, the group evaluated obituaries showing in the summertime of 2016 within the New York Occasions, the Singapore-based Strait Occasions and a neighborhood Charlottesville newspaper. Analysis assistants have been tasked with describing obituaries utilizing simply 12 adjectives, reminiscent of “safe” and “snug” for happiness, “fulfilling” and “sense of goal” for that means and “dramatic” and “eventful” for psychological richness. Obituaries that scored excessive in psychological richness additionally scored excessive in that means, however not happiness.

The analysis, showing on-line August 12 in Psychological Overview, discovered that main life occasions, reminiscent of divorce, profession adjustments and private tragedies, linked to greater richness, however not that means or happiness.

Nonetheless, Oishi and his group wanted to reply the plain: May such an intense, unpredictable and incessantly sad life actually be a path individuals desired? The researchers requested greater than 3,100 individuals throughout 9 nations — the US, Japan, South Korea, India, Singapore, Norway, Portugal, Germany and Angola — to attain 15 phrases just like these used within the obituary research on how intently the phrases described their best lives on a scale from 1 (in no way) to 7 (very a lot). A nine-term subset of the 15 phrases confirmed that for many nations, individuals’s best life was most characterised by happiness and least characterised by richness, the researchers reported June 2020 in Affective Science. Nonetheless, common richness scores ranged from 3.7 to five.62, suggesting that folks desired some richness of their lives.

On condition that ambiguity, the researchers then compelled contributors to decide on which life they desired most: completely satisfied, significant or wealthy. Fifty to 70 p.c of respondents selected phrases reflecting happiness and 14 to 36 p.c selected that means as their best life. Percentages different by nation, however a large minority — 7 to 17 p.c — selected a psychologically wealthy life.

When the researchers requested 1,611 individuals in the US and 680 individuals in South Korea if their lives would have been happier, extra significant or psychologically richer if they may undo their biggest remorse in life, roughly 28 p.c of People and 35 p.c of South Koreans reported that their lives would have been psychologically richer with a do-over.

“That implies to me that perhaps implicit in lots of people’s needs is psychological richness: ‘I want I had taken on that chance,’ ” Oishi says.

Puzzle meeting not mandatory

Not everybody, nonetheless, accepts the shift from a great life dichotomy to a great life triad. “There’s a bundle of conversations available about these conceptually tethered ideas,” says developmental psychologist Anthony Burrow of Cornell College. “As a result of for some individuals, isn’t it doable {that a} psychologically wealthy life is a lifetime of goal, is a lifetime of that means?”

The critique is legitimate. Because the obituary research confirmed, richness and its hyperlink to main, typically adverse, life occasions seems distinct from happiness. However these adverse life experiences can foster that means. A big physique of literature reveals, as an example, that pure disasters and different traumatic occasions can set off a phenomenon often known as post-traumatic development: a change that provides individuals a newfound appreciation for all times and a need to assist others (SN On-line: 4/3/19).

An experiment from a number of years in the past illustrates how this transformation performs out. Earlier than richness was in consideration, behavioral economist Kathleen Vohs of the College of Minnesota in Minneapolis sought to know that means and happiness in isolation, which was difficult as a result of completely satisfied individuals additionally have a tendency to guide lives excessive in that means and vice versa. The researchers recognized solely these variables linked to happiness, reminiscent of satisfying one’s wants and needs, or solely that means, reminiscent of spending time with one’s youngsters. Their findings, showing in 2013 within the Journal of Constructive Psychology, revealed that happiness in isolation is linked to a deal with the current whereas that means in isolation connects the previous, current and future, typically by self-reflection.

The excellence between that means and richness, as such, hinges on whether or not stitching collectively the strands of 1’s life, or coherence, is crucial to constructing a great life. Individuals who examine that means say sure; Oishi says no, turning to fiction to make his level. In Muriel Barbery’s 2006 novel The Class of the Hedgehog and Rabih Alameddine’s 2014 An Pointless Lady, the principle characters are poor and lonely ladies who’re neither curious about making the world a greater place nor really feel that their experiences add as much as some higher complete. As an alternative, the 2 ladies, Renée and Aaliya, pursue lives stuffed with consuming literature, artwork and music, Oishi says.

“Each ladies admire moments of ineffable magnificence, Proustian moments of elongated time and aesthetics, and lead a life stuffed with interior richness,” he and colleagues wrote in 2019.

Oishi’s proposition is easy, but radical: Experiences, whether or not principally vicarious as with Renée and Aaliya, or firsthand, can supply a great life with out summing as much as something higher than their components.

“Ideally, we need to have all three: happiness, that means and psychological richness,” Oishi instructed me in an e-mail. “However having only one is ample to guide a great life.”

The inventive impulse

After the neurological heavens opened, Sacks revealed his personal e book on migraines in 1970. He adopted it with Awakenings in 1973, documenting the miraculous restoration and relapse of catatonic sufferers who started to clap, stroll and speak after remedy with a medicine for Parkinson’s illness, earlier than fading again into unresponsiveness.

Regardless of his lifelong mental and inventive frenzy, Sacks remained ever alone. After a short fling at age 40, he was celibate for the following 35 years.

“He was not completely satisfied. He was inventive. He was productive. And he was shifting ahead,” Burns says. “And I feel if one is inventive, productive and shifting ahead, one is shifting towards happiness.”

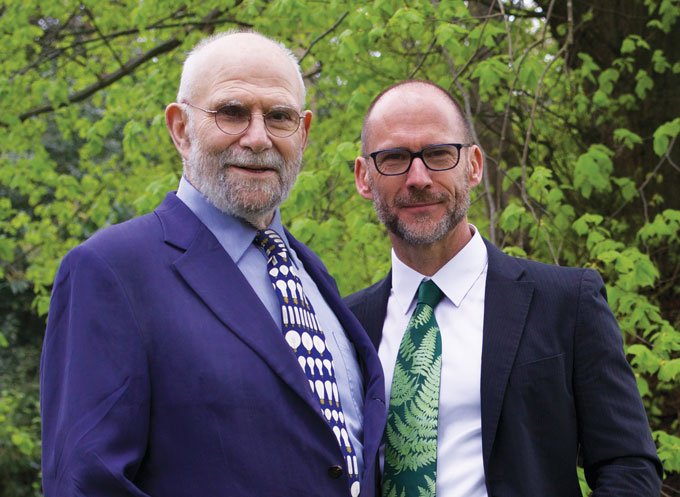

Oliver Sacks (left) discovered psychological richness and that means, due to his writings and interactions with sufferers. Discovering happiness took him till close to the tip of his life. When Sacks was in his late 70s, he met the love of his life, writer and photographer Invoice Hayes (proper).The Oliver Sacks Basis

Oliver Sacks (left) discovered psychological richness and that means, due to his writings and interactions with sufferers. Discovering happiness took him till close to the tip of his life. When Sacks was in his late 70s, he met the love of his life, writer and photographer Invoice Hayes (proper).The Oliver Sacks Basis

Although Burns makes use of the time period “inventive” casually, the pursuit of artwork appears uniquely suited to these looking for, or compelled into, a wealthy life. “Individuals who rating excessive in openness to expertise have a tendency to guide extra inventive lives,” says Oshin Vartanian, a cognitive neuroscientist on the College of Toronto.

And Oishi’s work has proven that aesthetic experiences enhance richness. As an example, in a 2020 examine within the European Journal of Character, Oishi and colleagues in contrast richness ranges between college students finding out overseas and college students who remained on campus. Although each teams began on the identical richness ranges, richness scores among the many college students finding out overseas went up after 12 weeks.

Pupil diaries revealed that the examine overseas college students participated in significantly extra creative actions, reminiscent of going to museums and live shows, than college students who remained on campus. Engagement with artwork, Oishi says, “defined partially why the examine overseas group had greater psychological richness.”

As COVID-19 variants ricochet across the globe, a fantastic many individuals are actually like these college students finding out overseas — not touring, however dosed in a distinct type of richness. Right here, on this international terrain, we too search magnificence.

Scientists have largely centered on the creative genius, the prototypic inventive, Vartanian says. However the pandemic means that we also needs to examine, and encourage, the on a regular basis inventive.

Vartanian counts himself amongst this on a regular basis lot. Through the pandemic shutdown, somebody gave him a damaged play construction for his youngsters. Vartanian couldn’t entry the components he wanted to repair it, so he realized the way to chisel and do woodwork to get the equipment in working order. “Doing issues I’d by no means finished earlier than,” Vartanian says, “was so drastically satisfying for me.”

I acknowledge the sensation. After I entered the pottery studio, I knew nothing of the craft. Merely centering the clay on the wheel took me seven classes. Whereas I can now heart small lumps of clay with relative ease, stunning varieties elude me. A half yr on, I’ve thrown misshapen bowls, a smattering of wobbly cups and precarious vases that fold on the neck. I’m, at my very own life’s midpoint, awash in imperfect vessels.

Gupta has created an assortment of wobbly vases, bowls and cups.Adam Goodenough

Gupta has created an assortment of wobbly vases, bowls and cups.Adam Goodenough

Finishing the triad

Within the Venn diagram of the great life, Sacks spent a lot of his time exterior all three circles. By midlife, although, psychological richness had change into his beacon.

But, in crafting his sufferers’ tales, Sacks made his life about one thing bigger than himself, Burns says. “He turned the mirror round [and said,] ‘I’m going to look outward with the intention to additionally look inward.’ ” Sacks had landed on the overlap between richness and that means.

Then, in his late 70s, Sacks fell deeply, head over heels in love. After a lifetime of battle, he lastly felt he belonged, not simply in literary or tutorial circles however inside himself. In that adieu, Sacks remarked: “My predominant feeling is considered one of gratitude. I’ve liked and been liked; I’ve been given a lot and I’ve given one thing in return; I’ve learn and traveled and thought and written.”

Gratitude, analysis reveals, is the language of happiness. On the sundown of his life, then, Sacks had arrived on the junction of these three paths.

He nailed the ending, Burns says. “That’s given to very, only a few of us.”