Tradition is a cherished value in MLB. But a new, rapidly-adopted technology — PitchCom— is already changing the game partway through its first season.

Chicago White Sox reliever Joe Kelly has worn his signature glasses on the mound for most of his career. At one point, Kelly even partnered with an eyewear company. This season, he doesn’t need to wear his glasses anymore.

By mid-July, New York Yankees games had been noticeably shorter compared to last season — by an average of five minutes.

Outfielders across the league are getting better reads on balls-in-play, and some people around the sport have noted that the game’s flow has noticeably improved compared to recent years.

These improvements have all been credited to PitchCom, a small electronic device worn by players, used mainly by the pitcher and catcher to communicate signs. Until now, players used a set of specially created hand signals to communicate on the field.

PitchCom was first introduced to MLB in 2020 by magicians and mentalists Craig Filicetti and John Hankins when the two business partners came up with a proposal for a product they had created to pitch to the league.

Initially, MLB had shelved plans to test PitchCom in live games due to the pandemic but began trials last season in the eight-team Low-A California League.

From there, thanks to the system’s success in the minors, PitchCom made its rapid ascension to approval for MLB-level use on April 5, just days before the new season was to begin.

“This sport moves like an iceberg,” said Chicago White Sox play-by-play announcer Len Kasper. “For PitchCom to not only be used experimentally in spring training but then to be approved to use during the season this year is kind of remarkable,” Kasper continued.

“I did not expect in spring training that this would be something that all these teams would use during the regular season … the buy-in over the first three months has been kind of breathtaking.”

Now, just four months after its league approval, all 30 MLB teams have used PitchCom, and many teams have incorporated its use into every game. It’s been praised by future Hall-of-Fame and Cy Young-caliber pitchers such as, Zack Grienke, Justin Verlander and Gerrit Cole, which seem like quite high watermarks.

The system already made a noticeable impact in several areas of the game that MLB has been looking to address. PitchCom’s main priority is concealing pitcher and catcher signs, something that has been a part of heightened sign-stealing paranoia throughout the league in the wake of the 2017 Houston Astros sign-stealing scandal.

In addition, communicating signs electronically has helped significantly improve pace-of-play, another top issue on MLB’s list of improvement goals.

So, after four months of usage around the league, what do we know about PitchCom, what kind of results is it yielding and what does its future in the game look like?

Jacob Stallings of the Miami Marlins hands over a Pitchcom unit to pitcher Zach Pop during a mound meeting in the fifth inning against the New York Mets at loanDepot park on June 25, 2022 in Miami, Florida. (Photo by Eric Espada/Getty Images)

How does the MLB PitchCom system work?

In November of 2021, several TV and radio broadcasters; including Milwaukee’s Brian Anderson and Chicago’s Len Kasper, Boog Scambi and Jason Benneti were invited to visit the Major League Baseball offices in New York. Intended to showcase the league’s latest tech advances for the coming season, the trip also included an introduction to a new pitch-calling system — PitchCom.

“We were all just blown away by the level of preparation, testing, all the things that have been put in place for the last few years,” said play-by-play announcer Brian Anderson of the presentation in New York.

“On the surface level, it feels like ‘Whoa, they just threw this [PitchCom] thing at us … what the heck is it?’ but actually it’s been in testing for a while,” Anderson continued, referring to its use in the minor leagues.

The PitchCom system, a patent-pending product that can be purchased for any level of baseball, consists of a small wearable keypad with nine buttons plus a toggle for volume adjustment, a 6-inch soft receiver worn in a player’s caps that uses a proprietary audio system incorporating bone-conducting hearing technology, and a small tube-style ear-piece attached to the catcher’s mask, which Anderson pointed out acts similarly to an IFV, the in-ear feed broadcasters use to communicate with crew members during games.

Catchers can wear the receiver attached to an armband on their wrist, or as most have now adopted, on their shin guard. The nine buttons are numbered and programmed by pitch types and locations. Catchers press their command for pitch type, followed by location, and the combination is then sent to the receivers via an encrypted channel.

“The negatives are like with any new technology, trying to figure out how best to use it when it’s loud,” Anderson said. “I think a lot of pitchers are putting it on their glove side ear, then they can put the glove over that ear, but you know, not everybody hears well out of both ears, so there are clearly challenges you have to overcome, but I think for the most part it’s been really positive for those who used it.”

MLB and PitchCom continue working together on evolving the system based on in-game usage feedback.

“I think a lot of teams are experimenting on what cuts through the noise better,” Anderson said of the receivers. “Does a high-pitched voice cut through better? Does a low baritone voice [work]? Now they’re actually going into the audiology part of things, like how does a human ear hear in traffic and noise? It’s all really interesting.”

Any voice can be recorded and programmed with the buttons on the receiver, so pitchers may be able to choose a voice based on depth, tone, and even their preferred language.

Anderson quipped that the idea of him or even Brewers radio legend Bob Uecker recording audio for the Brewers PitchCom receivers came up.

“The joke I have is like if the number nine button said ‘You can do it! You’re the best!’ You know, a little encouragement, if you didn’t need all nine spots, you could give them like an “I believe in you!”

According to sources, tech glitches or concerns around PitchCom have been minimal.

“The only thing I’ve observed is every once in a while it looks like they have to get a different device,” Kasper said. “So maybe … there’s a battery issue or [something].”

When there is a rare PitchCom-related hold up on the field, it’s often more for human-related error — some pitchers may forget to put the receiver in their cap before entering the field, volumes may need to be quickly adjusted, or simply the learning curve of having new technology to be responsible for, something that’s been a foreign concept in MLB dugouts until recently.

“Don’t forget the personnel that’s in charge of keeping all these batteries charged,” Anderson pointed out.

“All the different systems, it’s a monumental task and there’s a lot of pressure on these interns or whoever they’re using,” Anderson continued.

“If you go into the clubhouse [there’s] this table, and across this table are these charging stations and they’re for PitchCom, the tablets in the dugout, [the] people in charge of the technology [making] sure it’s all connected and working and charged … there’s like a whole team of people whose job it is to make sure this stuff works every day.”

Though Milwaukee Brewers pitcher Corbin Burnes was the first pitcher to use PitchCom in a regular-season game and continues to use it each start, Anderson says the rest of the Brewers staff has held out on using PitchCom for now.

“Corbin Burnes plowed through the difficulty of using a new piece of equipment, and now he is comfortable with it and uses it,” said Anderson.

“For the Brewers, it’s very simple, it’s nothing scientific,” Anderson continued. “I think the guys who started with it and don’t use it anymore … they’re just not comfortable with it, and pitching in the big leagues is hard enough … that’s one more element that they’re having to deal with … [maybe] it doesn’t feel right, it doesn’t sound right, they’re not getting the signals properly or consistently, some of that is technical [but] probably most of it is just the human side of it,” Anderson said.

“Just a new piece of technology when they’re already stretched to the max in their brain power, trying to perform at a very highly-skilled, high-level position.”

Kasper echoed similar sentiments about the demand that comes with asking a pitcher to change his routine in-season.

“You know the biggest thing that I’ve learned over the course of time is, it’s not just about the tech, it’s about a change in routine,” Kasper said. “Anything that changes even the tiniest bit of routine or, for lack of a better word, tradition in our sport is really, really difficult.”

Some pitchers simply have the type of relationship with their catcher, that they don’t feel the need to use PitchCom right now.

“There are a lot of pitchers who want to turn their brain off and just ride with Yadier Molina, and whatever he puts down they’re good with.” Anderson pointed out.

PitchCom has already undergone a few design changes. Anderson explained that the version of the system that’s currently being used has improved since his trip to New York.

“I saw two different versions, and this is the one they landed on,” Anderson said. “The one with the number, the keypads and the earpiece transmitter in the hat … I remember the first question coming up was “Why couldn’t you just [use] an Apple iPhone earbud?”,” Anderson continued. “But when you’re an athlete your balance, your whole being, how you gauge your surroundings, has a lot to do with what you hear and how you hear … you put in noise cancellation headphones you’ll hear great, but it’s going to throw your equilibrium off a bit.”

There had previously been a version that included a smartwatch-style interface, a design similar to a product that PitchCom is launching for baseball organizations starting in 2023, according to their website.

“There was one where I remember that it was like a watch, kind of a strap on the wrist on the gloveside [arm],” Anderson said, comparing it to an Apple Watch.

“What I remember of that is, they don’t want pitchers, especially with runners on base, having to look at a piece of equipment, because your concentration needs [to be on the runner],” Anderson explained. “The runner could take off and steal a base … They didn’t want guys looking at their wrist which could have more information, could be more detailed, so they went with the earpiece.”

Milwaukee Brewers catcher Victor Caratini types on a PitchCom on his right shine guard during the second inning of the game against the Baltimore Orioles at Oriole Park at Camden Yards. Mandatory Credit: Tommy Gilligan-USA TODAY Sports

Does PitchCom give some MLB teams and pitchers an unfair advantage?

The initial reaction to PitchCom by players, coaches, staff, and those around the game has been extremely positive. Though there are always those staunchly opposed to any changes made to the way the game is played — such as Mets pitcher Max Scherzer, who grabbed headlines during last month’s Subway Series, when he used the PitchCom system during his start, claiming postgame that it “should be illegal.”

“It works. Does it help? Yes. But I also think it should be illegal,” Scherzer told reporters postgame. “I don’t think it should be in the game.”

When asked if he will continue to use PitchCom, he stated that he might, and will continue to think about it.

“For me, I’ve always taken pride in having a complex system of signs and having that advantage over other pitchers,” Scherzer said.

While PitchCom takes away from what some consider the“tradition” of using hand signals, it isn’t trying to change the way the game is played, or take the control away from the players on the field.

“I feel like baseball did explore having the signals generated from the dugout, with somebody with all the information, but I agree with them on their assessment that you still want to keep it to the players on the field,” Anderson said.

“The college game has [tried] that, coaches are sending these signals and if you watch you can immediately tell how debilitated the game is,” Anderson continued, “These are four-hour games because before they punch a signal in, they’re going through data as fast as they can for every pitch,”

“I think Major League Baseball took a look at that and said that’s absolutely not what we want … I don’t want some game plan analyst in the dugout keying in pitches. Now you really are turning into a video game,” Anderson said.

“The game is losing some poetry anyway, so you’re trying to make sure that it doesn’t lose all that.”

By early August, many pitchers who had been a holdout on using PitchCom earlier in the season had gotten on board, including White Sox reliever Kendall Graveman. He told ESPN in May that a day may come when he uses the system, and that he wasn’t ruling it out.

“If you’re not using it, I think you’d feel really exposed and behind the eight-ball,” Kasper said.

“I think the idea of half the league was using it [and] half wasn’t, the half that wasn’t over the course of the first months was probably like “Hey, why aren’t we doing this?”

Cincinnati Reds starting pitcher Jeff Hoffman installs a PitchCom wearable device that transmits signals from catcher to pitcher in the sixth inning during a baseball game against the Milwaukee Brewers, Friday, June 17, 2022, at Great American Ball Park in Cincinnati.

The PItchCom system is finally speeding up MLB games

The 2017 Astros scandal illustrated that sign-stealing is a real issue that baseball struggles to control, which made teams respond to this threat more vigilantly than ever before. This began the era of pitchers and catchers using multiple sets of signs, changing them often throughout the game.

But it also began the era of longer and more frequent mound visits, tedious sign changing with a runner at second base, and longer games with less action.

“After the cheating scandal and trying to fix the sign stealing … the initial reaction to me ended up becoming drudgery,” Kasper explained of the sign switching method. “[With] the runner at second the game stopped, whatever pace there was [was gone] … there’s just too many step-out, step-off, go through the signs again,”

“That’s the part of the game that I think is least interesting to fans,” Kasper continued. “There’s no context to that other than ‘We need to start over because I don’t want somebody to know what I’m doing and PitchCom starts to cut a lot of that out. I think that’s a win all the way around.”

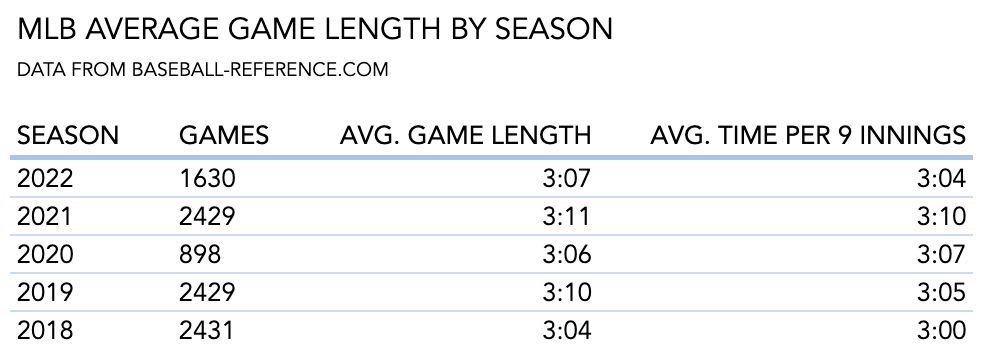

While the sign-switching method that teams began employing after 2017 made it harder for opposing teams to decode signs, the byproduct was a noticeably steady rise in game times across the league. But take a look at this season, a standard nine-inning game in 2022 is down by six minutes across the league compared to last season.

“It’s a significant difference in improving the rhythm of the game,” said Rangers play-by-play announcer Eric Nadel.

“It makes the game flow so much better. It used to be, a guy got to second base [and] here comes the waiting game,” Nadel continued, referring to the abrupt pause in action when signs changed due to the threat of the runner on second base decoding your current signs. “And it’s not like that anymore.”

Some teams saw a significant shift in their game times right away. The New York Yankees, who have been using PitchCom since spring training, lowered their average time this season by five minutes in the first half of the season. Here’s what Kristie Ackert of the New York Daily News wrote about that in June:

“Hashtag PitchCom,” Boone joked Sunday morning when talking about the quick game the Yankees played on Saturday. The Yankees don’t think it’s a coincidence that they’ve played 25 games under three hours this season. Through 54 games, that is about 47% of their games. Last season, the Yankees played just over 25% of their games at three hours or under.

Not every team has had this kind of measurable success yet though, Texas Rangers games have actually increased their average game time by one minute this season, compared to their 3-hour-and-5-minute mark last season. Nadel attributes some of this to other factors that don’t have to do with PitchCom.

“I know the game times haven’t gone down,” Nadel said. “But it’s not because of that, it’s because pitchers are still taking too much time between pitches in general,” he continued. “Relief pitchers are pitching more innings, they work slower than starters, batters are still being allowed to step out of the box,” he continued.

“But if it weren’t for PitchCom, the game would probably be another 5 minutes longer.”

Even the pitch calling exchange between pitcher and catcher can be made quicker when using PitchCom.

“Some guys get the signs well from the stretch with runners on,” Kasper said. “It feels like some guys almost get the signs before they even get on the rubber, you can kind of do it whenever you want at this point,” Kasper said of generating signs. “Because of the audio nature of it, you don’t have to really wait.”

Rays catcher Mike Zunino noted that the extra seconds PitchCom affords a pitcher on the mound could be used for recovery, or for a pitcher to refocus.

“If it can save them a couple seconds looking in [for signs] and it could get them in the right headspace to execute that pitch … maybe that’s all we need,” Rays catcher Mike Zunino told MLB.com in March.

“If [pitchers] have that extra time, maybe instead of having to look in, it gives you 2-3 extra seconds for recovery,” Zunino continued.

“Ultimately, the times we’ve used it, it’s really sped up the game.”

A detailed view as Francisco Lindor of the New York Mets wears a PitchCom receiver during the fourth inning against the Los Angeles Dodgers at Dodger Stadium on June 04, 2022 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Katelyn Mulcahy/Getty Images)

We’re just beginning to understand the potential for the PitchCom system

People in baseball who’ve been using the system this season have also noted the extra ways in which they can benefit from using PitchCom.

“They really like the fact that it’s not just pitches that are on there,” Nadel said of the Rangers coaching staff.

“They’ll put their coverages on there, what they’re going to do in a first and third situation or a possible bunt situation … the catcher can indicate that stuff too,” Nadel continued. “They can put in a call for a pick-off throw, or a pick-off play, they can put all that stuff in … they love the fact that the middle infielders know what’s coming, so it’s easier for them to properly position themselves on pitches.”

While no coaches or dugout staff are allowed to have a transmitter at any time, a rule that is closely monitored by an MLB rep, each club can equip five players on the field with a PitchCom receiver. The Brewers currently use it at pitcher, catcher, shortstop, second base and third base. Other teams have chosen to use it in centerfield.

Adding position players to the conversation by giving them receivers has been surprisingly effective, too.

“The benefit of not just your pitcher-catcher being able to communicate without signals,” Anderson said. “But then you add in the infielders and the centerfielder, I mean centerfielders are getting great jumps,” Anderson continued. “Some [outfielders] have great eyesight and can see the signals … but I’d say most don’t. So, it’s got a huge positive curve to it.”

On the field, players have also noticed these extra advantages provided by PitchCom, such as Texas Rangers utility man Brad Miller.

“It used to be if you’re not alert the whole time, you could miss the signs,” Miller told ESPN. “It’s way easier to be on every pitch like, ‘Hey, Aaron Judge is up there, you know that if it’s a fastball, it’s probably going one way and if it’s a curveball, it’s going this other way.’ It’s a softer focus.”

Kasper said that he believes eventually, everyone in the game will be using PitchCom.

“At the moment I would relate it to the c-flap,” Kasper said of PitchCom’s future.

“It’s not mandatory, but if you watch a game I would say, when you see a guy without a c-flap on his helmet, it almost stands out.” Kasper continued.

“That is not something that’s mandatory, but I think over the course of the next three or four years, it’ll be incredibly rare that a guy is not wearing [a c-flap], and I think the same goes for PitchCom.”

For some, the relief that comes with simply knowing your signs are protected, is enough of a benefit for them to continue using it.

“There will always be a crazy amount of paranoia no matter how much technology we have, that other teams are picking up signs,” Kasper said.

“That probably will never go away, but if it just cuts out a quarter of that, I think we’re winning,” Kasper said. “There’s no reason to use hand signals at this point in the game … it just doesn’t make sense to expose your sign when there’s such an easy way to not do it that way.”

PitchCom is still in the early stages of its adoption by MLB teams, and once feedback begins rolling in, there will likely be design changes ahead for the device — and some may still be related to sign-stealing.

“The one thing they told me is the catcher still kind of needs to hide where he’s pressing on the [keypad],” Nadel said.

“People are trying to steal that, I don’t know how the hell they do that,” Nadel continued with a laugh. “But apparently, there’s a way to do that.”

Even though the buttons are marked uniformly by number across devices, making it nearly impossible to recognize the details a catcher is entering, Nadel and Kasper both noted that backstops are still taking extra steps to protect their keypad entries.

“That also speaks to the paranoia when you think about it, that you’re covering a button that, even if you saw him hit the third button from the left, you might not have any idea what it is, they’re still trying to hide that.” Kasper said.

Nearly every major-league catcher that uses PitchCom now places the keypad on their shin guard to easily protect their entries with their glove. Anderson suspects that MLB and PitchCom could take note of that in the future.

“I love that they’re able to cover those keypads with their gloves,” Anderson said of the shin guard placement of the keypad. “I’m sure they’re looking at ways to make it smaller, better … maybe it’ll be more protected, [or] built into the shin guard at some point.”

Jose Cuas of the Kansas City Royals leans down to look for the catchers signs as they face the San Francisco Giants in the bottom of the sixth inning at Oracle Park on June 13, 2022 in San Francisco, California. (Photo by Michael Urakami/Getty Images)

PitchCom is working, even if some fans and players still have reservations

Over the last several seasons, MLB’s efforts to address its dire pace-of-play issues have been small so far, but felt like significant losses of the game’s character, while the return for these losses has been menial at best. After these changes, games failed to become noticeably short in any meaningful way.

Fans of the game have lost things that some considered treasured details of a timeless game — the four-pitch intentional walk, the “left-handed specialist” reliever, and soon, the hotly-debated pitch clock will be implemented.

So far, none of the efforts that the league has made towards their pace-of-play goals, including limiting mound visits, have had the sort of direct impact on the issue that PitchCom has. PitchCom has managed to impact the game in a meaningful way, while also seamlessly integrating itself, both to those on the field and the viewers.

Players who use PitchCom are satisfied, coaches are happy with it, and most fans hardly notice that it’s being used — something that should continue to be a goal in MLB’s future pace-of-play initiatives. That’s quite the success after just half a season.

For some, watching a catcher put down a complex set of hand signs with his pitcher is one of those timeless traditions of the game that fans don’t want to see eliminated, one that PitchCom will soon all but do away with.

But going forward, teams will be better protected from sign theft, games will get shorter, players will be more connected on the field, and the game’s viewing experience will be more polished and enjoyable than it has been in years.

That sort of trade-off certainly sounds like poetry to me.

Check out more great baseball stories from FanSided Features.