Conor Bradley is sidelined with what was initially anticipated to be a minor setback but is, in fact, a stress fracture in his back that will require time to heal.

Liverpool’s young and multi-talented defender showed promise in the opening games of the pre-season, but then did not make the trip to Singapore or return for the remainder of pre-season.

His injury was initially described as “minor” but he was then left out of international duty with Northern Ireland, with an update that he suffered a stress fracture in his back that would keep him out for two to three months at minimum.

Moreover, Northern Ireland manager Michael O’Neill stated there is “extreme doubt” that Bradley will participate during the remainder of the Euro 2024 qualifiers (which end in mid-November). That would put his timescale on the tail-end of 12 weeks.

So how did the injury go from being a mild issue to multiple months out, and just how serious is it? Lets take a closer look, starting with the injury itself.

What’s a stress fracture?

A stress fracture is weakening in a bone, most commonly due to repetitive stress and load on that area.

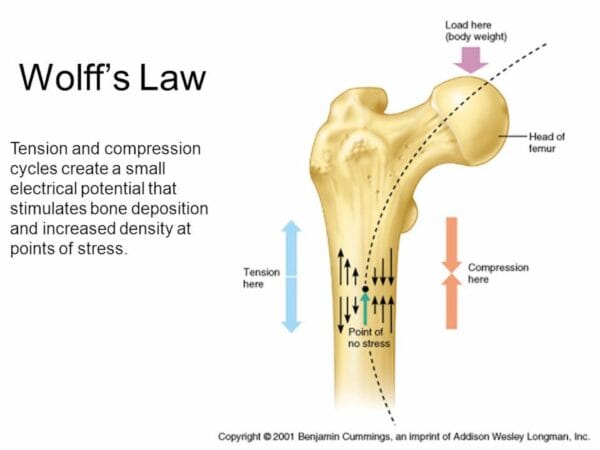

Bone is constantly breaking down when stress is placed upon it and then building back up (called ‘remodeling’) – it is how bone gets stronger. This adaptation of bone to the stress placed upon it is called ‘Wolff’s Law’.

The same principle applies for many structures in the body.

However, when the ratio of stress to rebuilding becomes misaligned (for example, through repetitive load) then it can lead to weakening in the bone and a stress fracture due to overload.

In Bradley’s case – a stress fracture in the back – he most likely has a stress fracture to a bone (vertebra) in the lower back.

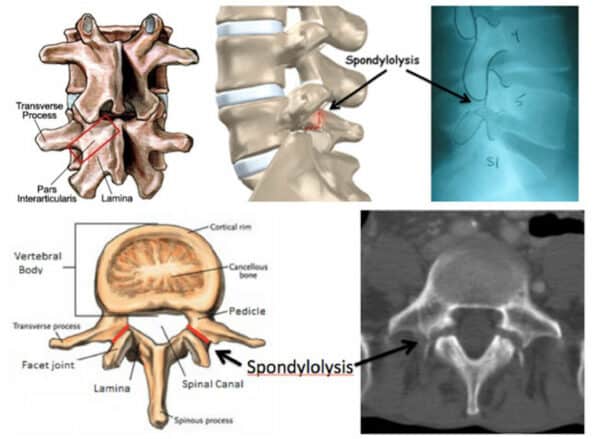

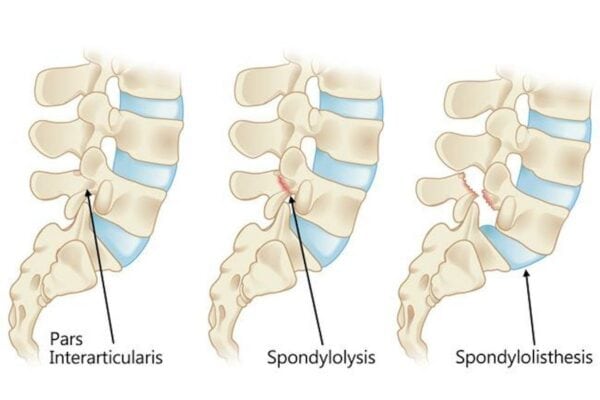

More specifically, he most likely has a stress fracture to the pars interarticularis, a structure which makes up part of the vertebra. This is termed a ‘spondylolysis’ (say that three times fast!).

These injuries are not uncommon in younger, elite athletes who play dynamic sports, particularly ones that require repetitive trunk movements as football does. There’s constant trunk bending, extending, rotation and often times under strain and load from opponents.

Aligning with that, Northern Ireland gaffer O’Neill further commented that “those are injuries that sometimes occur in young players.”

In Conor’s case, the injury would make sense when looking at the full context of last season, where he played in many games at a higher intensity level – he played more minutes for club and country than any other teenager in world football last season (4,723).

The cumulative increase in games and intensity combined with the repetition could lead to that overload mentioned before.

A similar example is Calvin Ramsay, who most likely had the same injury and he missed three months. Arsenal centre-back William Saliba also likely had a similar issue (although lesser severity) that cost him the final third of last season.

Speaking of severity…

How did the injury go from mild to months out?

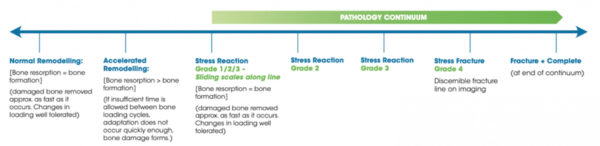

Thus far, we have only discussed stress fractures as if they were a static, binary entity. However, stress fractures actually exist on a continuum of bone stress injuries (BSI), summarised in this graphic:

As you can see, a stress fracture is farther down the continuum of bone stress injuries with multiple stages before it.

However, it can be difficult to fully discern the specific stage of the injury, particularly in the early days, because there is significant grey area and they don’t always show up reliably on imaging.

Often times, there will be some observation period where you assess how the injury is evolving and that will give you more information on severity.

In the case of stress reactions, they can often be managed on a week to week basis to see how the player responds and then decide on availability, whereas with over stress fractures, there’s much more risk.

This diagnostic process would help explain why Bradley’s injury went from mild to months out. It may have initially been deemed as a stress reaction but then, based on further examinations and imaging, deemed a stress fracture that needs more time to heal.

Additionally, if the stress fracture is indeed a spondylolysis, there’s even more cause for caution because if not managed appropriately it can potentially lead to a an overt fracture in the bone – termed a ‘spondylolisthesis’ – and potentially compromise other regions in the spine as well.

How concerning is this injury?

I understand any mention of a back injury can immediately send a shiver down many people’s spines (yes, I know what I did there), but it is never quite that simple.

In this case, provided this is the injury I believe it to be for the reasons I have laid out, the outcomes are quite good with proper management and rehabilitation.

Further, the relatively high prevalence of the injury in young, elite athletes also means the processes for treating it tends to be of greater quality due to a larger sample size of dealing with this injury.

Overall, I expect Bradley to make a full recovery in the excellent hands of the Liverpool medical team and be properly bedded back in when he is available to return.