The Mind in Search of Itself

Benjamin Ehrlich

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $35

Spanish anatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal is named the daddy of contemporary neuroscience. Cajal was the primary to see that the mind is constructed of discrete cells, the “butterflies of the soul,” as he put it, that maintain our reminiscences, ideas and feelings.

With the identical unflinching scrutiny that Cajal utilized to cells, biographer Benjamin Ehrlich examines Cajal’s life. In The Mind in Search of Itself, Ehrlich sketches Cajal as he moved by way of his life, capturing moments each mundane and extraordinary.

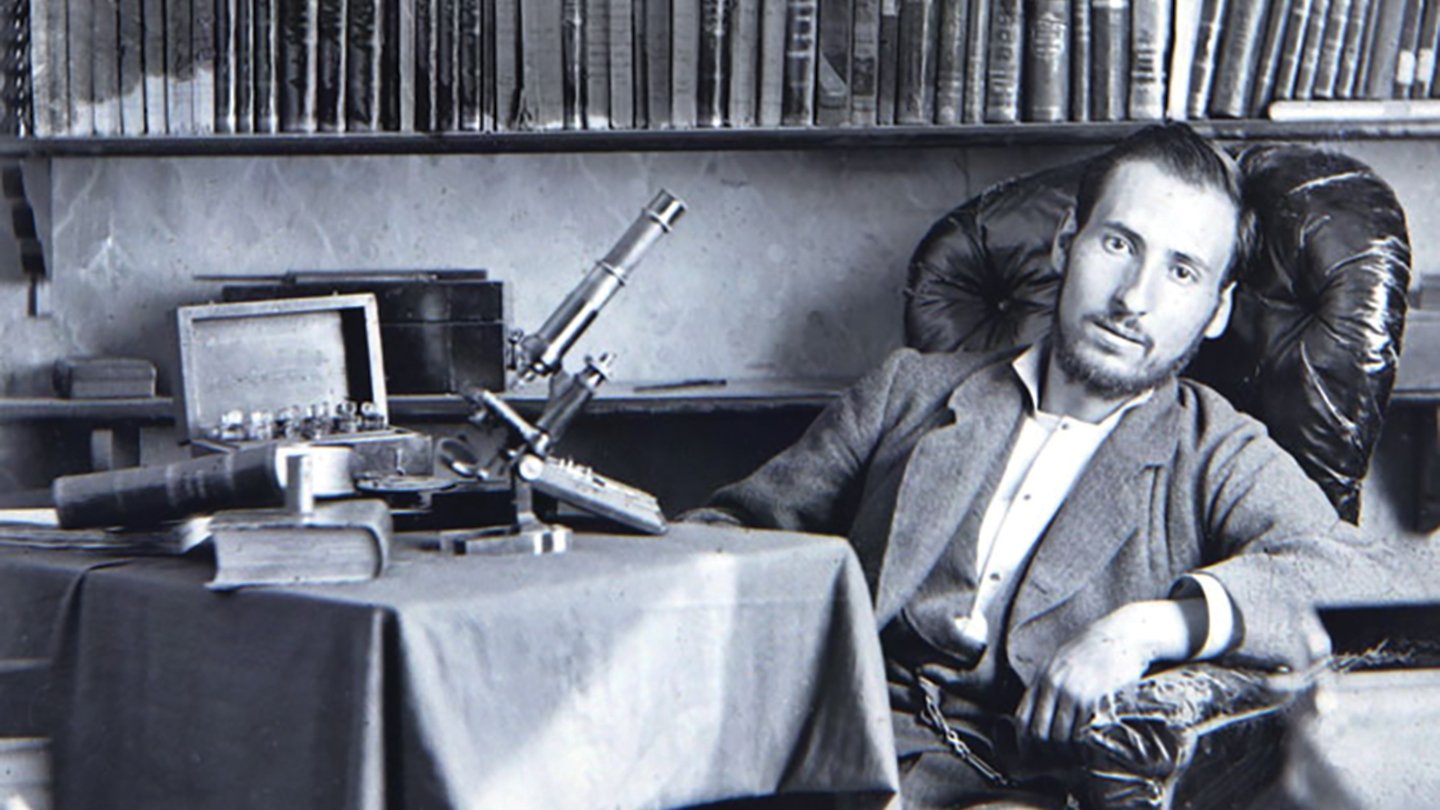

Among the portraits present Cajal as a younger boy within the mid-Nineteenth century. He was born within the mountains of Spain. As a toddler, he yearned to be an artist regardless of his disapproving and domineering father. Different portraits present him as a barber-surgeon’s apprentice, a deeply insecure bodybuilder, a author of romance tales, a photographer and a navy doctor affected by malaria in Cuba.

The ebook is meticulously researched and totally complete, overlaying the time earlier than Cajal’s beginning to after his loss of life in 1934 at age 82. Ehrlich pulls out vital moments that convey readers inside Cajal’s thoughts by way of his personal writings in journals and books. These glimpses assist situate Cajal’s scientific discoveries throughout the broader context of his life.

Signal Up For the Newest from Science Information

Headlines and summaries of the newest Science Information articles, delivered to your inbox

Thanks for signing up!

There was an issue signing you up.

Arriving in a brand new city as a toddler, as an example, the younger Cajal wore the flawed garments and spoke the flawed dialect. Embarrassed, the delicate little one started to behave out, combating and bragging and skipping faculty. Round this time, Cajal developed an insatiable impulse to attract. “He scribbled continuously on each floor he may discover — on scraps of paper and faculty textbooks, on gates, partitions and doorways — scrounging cash to spend on paper and pencils, pausing on his jaunts by way of the countryside to sit down on a hillside and sketch the surroundings,” Ehrlich writes.

Cajal was all the time a deep observer, whether or not the topic was the stone wall in entrance of a church, an ant attempting to make its means residence or dazzlingly sophisticated mind tissue. He noticed particulars that different folks missed. This expertise is what finally propelled him within the Eighteen Eighties to his massive discovery.

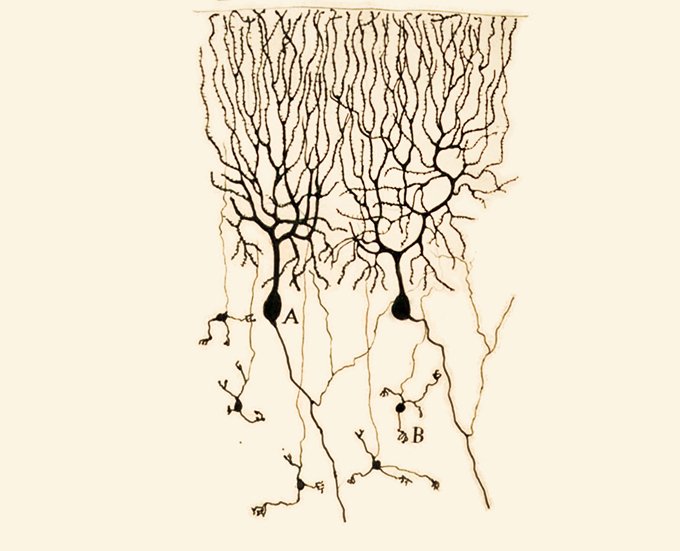

On the time, a prevailing idea of the mind, referred to as the reticular principle, held that the tangle of mind fibers was one unitary entire organ, indivisible. Peering right into a microscope in any respect types of nerve cells from all types of creatures, Cajal noticed over and over that these cells in truth had house between them, “free endings,” as he put it. “Impartial nerve cells have been in all places,” Ehrlich writes. The mind, subsequently, was fabricated from many discrete cells, all with their very own totally different shapes and jobs (SN: 11/25/17, p. 32).

Cajal’s observations finally gained traction with different scientists and earned him the 1906 Nobel Prize in physiology or medication. He shared the prize with Camillo Golgi, the Italian doctor who developed a stain that marked cells, referred to as the black response. Golgi was a staunch proponent of the reticular principle, placing him at odds with Cajal, who used the black response to indicate discrete cells’ endings. The 2 males had not met earlier than their journey to Stockholm to attend the awards ceremony.

By his detailed drawings, Santiago Ramón y Cajal revealed a brand new view of the mind and its cells, equivalent to these two Purkinje cells that Cajal noticed in a pigeon’s cerebellum.Science Historical past Photographs/Alamy Inventory Picture

By his detailed drawings, Santiago Ramón y Cajal revealed a brand new view of the mind and its cells, equivalent to these two Purkinje cells that Cajal noticed in a pigeon’s cerebellum.Science Historical past Photographs/Alamy Inventory Picture

Cajal and Golgi’s irreconcilable concepts — and their hostility towards one another — got here by way of clearly from speeches they gave after their prizes have been awarded. “Whoever believed within the ‘so-called’ independence of nerve cells, [Golgi] sneered, had not noticed the proof carefully sufficient,” Ehrlich writes. The following day, Cajal countered with a exact, forceful rebuttal, detailing his work on “almost all of the organs of the nervous system and on a lot of zoological species.” He added, “I’ve by no means [encountered] a single noticed reality opposite to those assertions.”

Cajal’s fiercely defended insights got here from cautious observations, and his intuitive drawings of nerve cells did a lot to persuade others that he was proper (SN: 2/27/21, p. 32). However because the ebook makes clear, Cajal was not a mere automaton who copied precisely the article in entrance of him. Like all artist, he noticed by way of the extraneous particulars of his topics and captured their essence. “He didn’t copy photographs — he created them,” Ehrlich writes. Cajal’s insights “bear the distinctive stamp of his thoughts and his expertise of the world wherein he lived.”

This biography attracts a vivid image of that world.

Purchase The Mind in Search of Itself from Bookshop.org. Science Information is a Bookshop.org affiliate and can earn a fee on purchases created from hyperlinks on this article.