Financial advantage in football doesn’t guarantee success, but it can moderate failure.

No matter the number of zeros on the end, financial disparity exists across almost all levels of football.

At non-league level, we’ve seen Wrexham shoot up the divisions; in Scotland, Celtic then Rangers dominate financially, and the gap between the Premier League‘s Luton Town and Man City is colossal.

It is easy to moan about clubs that aren’t your own spending millions on players and blowing your own team’s plans out the water. We all do it, well Liverpool supporters do anyway – and so we should.

Being able to pay astronomically bigger wages, transfer fees and agent’s bonuses gives clubs an unfair advantage but, to paraphrase The Beatles, ‘money can’t buy you love success’.

It seemed almost surreal when Liverpool’s British record £110 million bid for Moises Caicedo was trumped by Chelsea and followed by a surprise move for Romeo Lavia, for whom the Reds were also rejected.

Suggestions that Al-Ittihad could pay more than £200m for Mo Salah leave fans with a feeling of helplessness. For better or worse, there is almost complete player power.

Money isn’t everything – for now

Thankfully, for clubs like Liverpool, who still aim to compete at the very top without the resources of oil-rich nations, having money doesn’t always equate to success.

While finances are the biggest factor, it is still possible for certain clubs to compete when they get things right, when everything goes to plan, when everything is perfect.

But therein lies the problem. For clubs without the vast wealth of Man City, Chelsea or Newcastle, in the Premier League‘s case, it is rare for everything to come together to create a perfect concoction for success.

Liverpool’s margin for error is smaller, and it is something that Jurgen Klopp has perhaps become hung up on with regard to transfer business.

But, can you blame him?

The fact he missed out on two league titles, despite earning nearly 100 points each time, must haunt him.

That empty feeling

In 2019, there were 24 hours in particular when being a Liverpool supporter felt very strange.

There we were, about to reach 97 points in the Premier League, yet we still wouldn’t lift the trophy due to Vincent Kompany’s freakish long-range winner vs. Leicester.

Despite a half-decent performance at the Nou Camp, the Reds were also about to be knocked out in the Champions League semi-finals, or so we thought.

To the relief and elation of fans, Liverpool triumphed against all the odds and won the European Cup that year, giving the team energy and confidence to go again the next season.

But, during those 24 hours, there was a strange mix of pride and emptiness as a supporter.

How could we be so good and still not win?

It renders the sport almost pointless when there is an absence of competitiveness, it is the essence of football.

People love the game because, on their day, anyone can beat anyone. While this is still true, tangible instances are becoming fewer and further between.

In Germany, Bayern Munich have won 11 consecutive Bundesliga titles. Closer to home, Man City have won five of the last six with only Liverpool breaking their spell of supremacy.

When does money help?

Like mentioned in the introduction to this piece, financial advantage doesn’t guarantee success but it can moderate failure.

Of course, the Reds aren’t nobodies and are far better off than the vast majority of football clubs; Liverpool’s title surely gave solace to those other clubs hoping to one day challenge.

For this reason, it is difficult to understand why supposed neutrals would prefer Man City to win the league over Klopp’s team. Tribalism takes over, but a vote for Man City is surely a vote for predictability and hegemony.

These aren’t values the world-beating ‘Barclays Premier League TM’ purportedly champions.

Where the super-rich have their advantage is that the risks they take have smaller consequences.

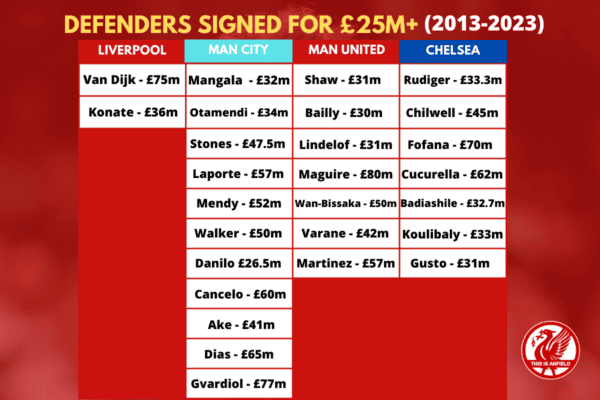

In the last 10 years, Man City have signed 11 defenders for over £25 million. Liverpool have signed just two.

This, in essence, is the issue. Man City can afford to spend repeatedly with little consequence. If they throw enough darts at a board, one will hit bullseye.

Liverpool cannot afford to do this. All this creates for a platform on which the super-rich continually dominate because, no matter how wrong they get it in the transfer market, they are able to rectify the problem.

It creates an uneven playing field and the same clubs stay at the top, something that some Man City supporters have used as an argument against Financial Fair Play.

The premise of FFP was to prevent clubs spending far more than they earned. However, loopholes have been used to circumvent these rules and a lack of real consequence, for Man City and Chelsea in particular, has meant that FFP has is now almost trivial, for the top clubs at least.

With Saudi Arabian investment, Newcastle are the latest club on the scene. While spending big – their net spend is approximately £350m since the takeover – they aren’t treating FFP with as much blasé as others have in the past.

They are less kid in a sweet shop and more builder at B&Q, albeit one with funders that have no desire to implement free speech in their country.

Chelsea, who were the original oil-funded Premier League project, when Roman Abramovich bought the club in 2003, have been one of those to splash the cash in recent years.

With Todd Boehly acting as figurehead of the group that bought Chelsea in 2022, the Londoners were taken over by a consortium backed by investment firm Clearlake Capital.

The Saudi Arabian sovereign wealth fund (PIF), that bought Newcastle, reportedly have “billions of pounds of assets managed by Clearlake.”

It was no coincidence that N’Golo Kante, Edouard Mendy and Kalidou Koulibaly all left for clubs in the Saudi Pro League fully controlled by the PIF, this summer.

Despite their recent lavish spending, nearly £1 billion in the last couple of years, Chelsea look like they will be battling for a Europa League spot rather than the league title.

Newcastle have spent less than Chelsea since their new owners came in, yet have made significantly more ground than Boehly’s Blues.

There has been a more methodical approach in the transfer market, as opposed to Chelsea‘s strategy which appears to have been to buy anyone and everyone, no matter what the cost.

What about everyone else?

The point of all this articulating is that other clubs are finding it increasingly hard to compete.

The ‘Moneyball’ strategy that FSG tried to implement when they arrived at Liverpool can still work to some extent – just look at Brighton, but they are not competing at the very top.

Without someone who can work miracles, like Klopp, consistent success is becoming increasingly unattainable for the mere mortals of the football world.

Soon it will take just that, a miracle, for anyone but oil-rich or state-owned football clubs to become the best.

This is in-part why clubs such as Liverpool, Man United and Barcelona signed up for the European Super League. It was some kind of guarantee that they would still be able to sit at the top table of football.

The collapse of that specific project, for now, was one factor in FSG’s willingness to sell the club.

Of course, for the ordinary fan who just wants to see their team play well each week, super leagues and human rights-abusing states controlling football are far from enjoyable to contemplate.

That isn’t to say we live in a perfect world ourselves, but football is increasingly distancing itself from normal supporters, but this is nothing new.